Most people know about LDL cholesterol - the "bad" kind that clogs arteries. But there’s another cholesterol particle hiding in plain sight, quietly raising your risk of heart attack and stroke, even if your LDL is perfect. It’s called lipoprotein(a), or Lp(a). And if you’ve never heard of it, you’re not alone. Despite affecting 1 in 5 people worldwide, Lp(a) is rarely tested, rarely discussed, and often missed by standard blood work.

What Exactly Is Lipoprotein(a)?

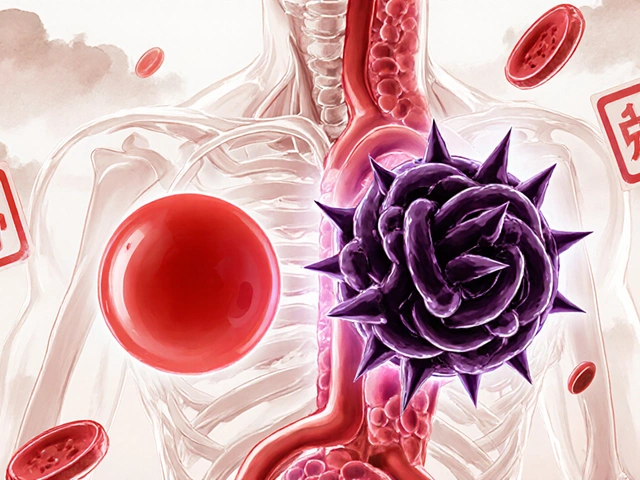

Lp(a) is a unique type of cholesterol-carrying particle. Think of it like an LDL particle - the kind doctors usually worry about - but with a strange extra protein stuck to it called apolipoprotein(a). This extra piece doesn’t just make it different; it makes it dangerous. That protein has sticky, knot-like structures called kringle domains that latch onto damaged areas in your arteries and block your body’s natural cleanup system. Instead of helping clear plaque, Lp(a) helps build it. It also makes blood clots harder to break down, increasing your risk of sudden heart attacks and strokes.

Unlike regular cholesterol, Lp(a) isn’t influenced much by what you eat or how much you exercise. It’s mostly written in your genes. In fact, 70% to 90% of your Lp(a) level is determined by your DNA - more than almost any other cardiovascular risk factor. That means if your parent has high Lp(a), you have a 50% chance of inheriting it. It’s not something you can fix with a salad or a treadmill. It’s something you’re born with.

Why Is Lp(a) So Dangerous?

High Lp(a) doesn’t just add to your heart disease risk - it can double or triple it, even if everything else looks normal. Studies show that levels above 50 mg/dL (or 105 nmol/L) are linked to a significantly higher chance of:

- Coronary artery disease

- Heart attack

- Stroke

- Peripheral artery disease

- Aortic valve stenosis - a condition where the heart’s main valve narrows, forcing the heart to work harder

What’s scary is that people with Lp(a) levels above 90 mg/dL (190 nmol/L) have a risk equivalent to someone with familial hypercholesterolemia - a well-known, serious genetic cholesterol disorder. And here’s the kicker: you might feel fine. No chest pain. No symptoms. Just a ticking time bomb in your bloodstream.

One of the biggest problems? Lp(a) doesn’t show up on routine cholesterol tests. Your doctor won’t see it unless they specifically order a test for it. That’s why so many people only find out they have high Lp(a) after they’ve already had a heart attack or their parent died young of heart disease.

Who Should Get Tested?

Not everyone needs a Lp(a) test. But if any of these apply to you, you should ask your doctor:

- You or a close family member had a heart attack, stroke, or sudden cardiac death before age 55 (men) or 65 (women)

- You’ve been diagnosed with familial hypercholesterolemia

- You have early or severe atherosclerosis despite normal LDL levels

- You have aortic valve stenosis without other obvious causes

- You have a family history of high Lp(a)

Black individuals tend to have higher Lp(a) levels on average than white, Hispanic, or Asian populations. Women often see their Lp(a) levels rise after menopause, likely because estrogen - which helps suppress Lp(a) - drops. But no matter your background, if your level is high, your risk is high.

Current Treatment Options - And the Big Limitation

This is where things get frustrating. There’s no magic pill to lower Lp(a) - yet.

Statins, the go-to cholesterol drugs, don’t help. In fact, they might nudge Lp(a) levels up slightly. Niacin (vitamin B3) can reduce Lp(a) by 20-30%, but it causes flushing, liver stress, and doesn’t clearly lower heart attacks in studies. Lifestyle changes? Diet, exercise, weight loss - they help your overall heart health, but they barely touch Lp(a). You can’t out-exercise your genes.

That’s why so many people with high Lp(a) are told, "Just focus on lowering your LDL and blood pressure." And that’s still good advice - because the more risk factors you stack up, the higher your chance of disaster. But it’s not enough. If your Lp(a) is sky-high, you need more than just general heart health tips.

The Promise of New Drugs - What’s Coming in 2025

There’s real hope on the horizon. A new class of drugs called antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs) is showing dramatic results. One drug, pelacarsen, has been shown in trials to slash Lp(a) levels by up to 80%. That’s not a small drop - that’s a game-changer.

The big question is whether lowering Lp(a) actually prevents heart attacks and strokes. That’s what the Lp(a) HORIZON Outcomes Trial is trying to answer. This phase 3 trial is tracking thousands of high-risk patients with Lp(a) above 430 nmol/L (90 mg/dL). Results are expected in late 2025. If the data shows fewer heart events, this could become the first treatment specifically approved to target Lp(a).

Other drugs are in the pipeline too - including RNA-based therapies that work similarly. If approved, these would be the first treatments designed to attack Lp(a) at its source: the liver, where it’s made.

What You Can Do Right Now

While we wait for new drugs, here’s what actually matters:

- Get tested. If you’re in a high-risk group, ask your doctor for a specific Lp(a) blood test. Don’t assume your lipid panel covered it.

- Lower your other risks. If your Lp(a) is high, your LDL should be as low as possible. Aim for under 70 mg/dL, especially if you already have heart disease. Control your blood pressure. Don’t smoke. Manage diabetes if you have it.

- Know your family history. Talk to relatives. If someone had a heart attack in their 40s or 50s, that’s a red flag. Encourage them to get tested too.

- Stay informed. The field is moving fast. New guidelines from the American Heart Association and American College of Cardiology now recommend universal screening for Lp(a) at least once in adulthood. That’s a big shift - and it’s coming to clinics soon.

High Lp(a) doesn’t mean you’re doomed. It means you need to be more proactive. You can’t change your genes. But you can change how you manage your heart health around them.

Final Thought: Silence Is the Real Risk

Lp(a) has flown under the radar for decades. Doctors didn’t have the tools. Patients didn’t know to ask. But now we know. We know it’s common. We know it’s genetic. We know it’s dangerous. And we’re on the verge of having the first real treatment.

The biggest risk isn’t having high Lp(a). It’s never finding out you have it.

Is Lp(a) the same as LDL cholesterol?

No. Lp(a) is a separate particle that contains an LDL-like core but has an extra protein called apolipoprotein(a) attached to it. This makes it more likely to stick to artery walls and interfere with blood clot breakdown. While LDL contributes to plaque, Lp(a) adds inflammation and clotting risks on top of that.

Can diet and exercise lower Lp(a)?

Not significantly. While healthy eating and regular exercise are vital for overall heart health, they have little to no effect on Lp(a) levels. This is because Lp(a) is mostly controlled by your genes, not your lifestyle. That’s why lowering other risk factors - like LDL cholesterol and blood pressure - becomes even more important if you have high Lp(a).

How do I know if I have high Lp(a)?

You need a specific blood test. Standard cholesterol panels don’t include Lp(a). Ask your doctor to order an Lp(a) test, especially if you have early heart disease, a family history of heart attacks before age 60, or aortic valve stenosis. Levels above 50 mg/dL (or 105 nmol/L) are considered high risk.

If my Lp(a) is high, will I definitely have a heart attack?

No. High Lp(a) increases your risk - but it doesn’t guarantee an event. Many people with elevated levels live long lives without heart problems, especially if they manage other risk factors tightly. Think of it like a loaded gun: it doesn’t fire on its own, but the risk is much higher if you pull the trigger - or in this case, if you also have high blood pressure, smoking, or high LDL.

Are there any supplements that lower Lp(a)?

No reliable supplements have been proven to lower Lp(a) in clinical studies. Some claim niacin or fish oil helps, but niacin’s effect is modest and comes with side effects, and fish oil doesn’t meaningfully reduce Lp(a). Avoid unproven products - they waste money and distract from proven strategies like lowering LDL and controlling blood pressure.

When will new Lp(a) drugs be available?

The first targeted therapy, pelacarsen, is expected to be approved in 2025 or 2026, depending on the results of the ongoing phase 3 trial. If successful, it will be the first drug specifically designed to reduce Lp(a) and prevent heart events. Until then, managing other risk factors remains the standard of care.

Margo Utomo

Lp(a) is the silent killer no one talks about 😔 I had a cousin drop dead at 48-no warning, no symptoms. Turns out his Lp(a) was through the roof. If we’d known? Maybe he’d be here. Get tested. Seriously. 🩸❤️

Matt Wells

The assertion that Lp(a) is unaffected by lifestyle is an oversimplification. While genetic determinism dominates, emerging evidence suggests that certain dietary patterns-particularly those low in refined carbohydrates and high in omega-3 fatty acids-may modestly modulate Lp(a) expression through epigenetic pathways. One must not conflate genetic predominance with genetic inevitability.

George Gaitara

So let me get this straight-your genes screw you over, doctors ignore it, and the only solution is waiting for some fancy drug in 2025? Meanwhile, Big Pharma is already lining up their billion-dollar pricing. This isn't medicine. It's a scam with a lab coat.

Deepali Singh

The data is inconsistent across ethnic groups. Why is the 1 in 5 statistic cited without acknowledging the higher baseline in Black populations? This feels like universal screening being pushed without considering how it exacerbates healthcare disparities when treatment remains inaccessible.

Sylvia Clarke

I love how this article doesn’t just throw facts at you-it gives you agency. You can’t change your genes, but you can change your vigilance. 🧠💡 I’m 52, post-menopause, and my Lp(a) came back at 120. My doc shrugged. I demanded an LDL target of 50. Now I’m on a PCSK9 inhibitor. I’m not scared-I’m strategic. And yes, I made my sister get tested. She’s high too. We’re turning family history into family power. 💪❤️

Jennifer Howard

I find it deeply concerning that this article encourages testing without emphasizing the psychological toll of knowing one has an unmodifiable, life-threatening risk. Many individuals are not emotionally equipped to handle the burden of genetic fatalism. Why are we not discussing counseling protocols alongside screening? This is reckless public health messaging.

Abdul Mubeen

Let’s be honest-this is all a distraction. The real cause of heart disease is inflammation from processed foods, glyphosate in the food supply, and the fact that the FDA approves drugs based on lobbying, not science. Lp(a) is just the latest boogeyman to sell tests and drugs. Wait until you see the next one-maybe your mitochondria are cursed.

mike tallent

I’m a nurse and I’ve seen this too many times. Patient comes in with perfect LDL, no symptoms, then has a heart attack at 50. We test Lp(a) after and it’s 200. If we’d known? We could’ve started them on a PCSK9 years ago. Please, if you’re in a high-risk group-ask. Don’t wait for the crash. 🩺❤️