Most people think when a drug’s patent expires, generics can jump in and lower prices. That’s not how it works anymore. In reality, many brand-name drugs stay protected for over 15 years-even after the original patent runs out-thanks to a web of hidden regulatory tricks called market exclusivity extensions. These aren’t patents. They’re legal loopholes built into drug approval rules that let companies delay generic competition long after their core patent expires.

What Market Exclusivity Actually Means

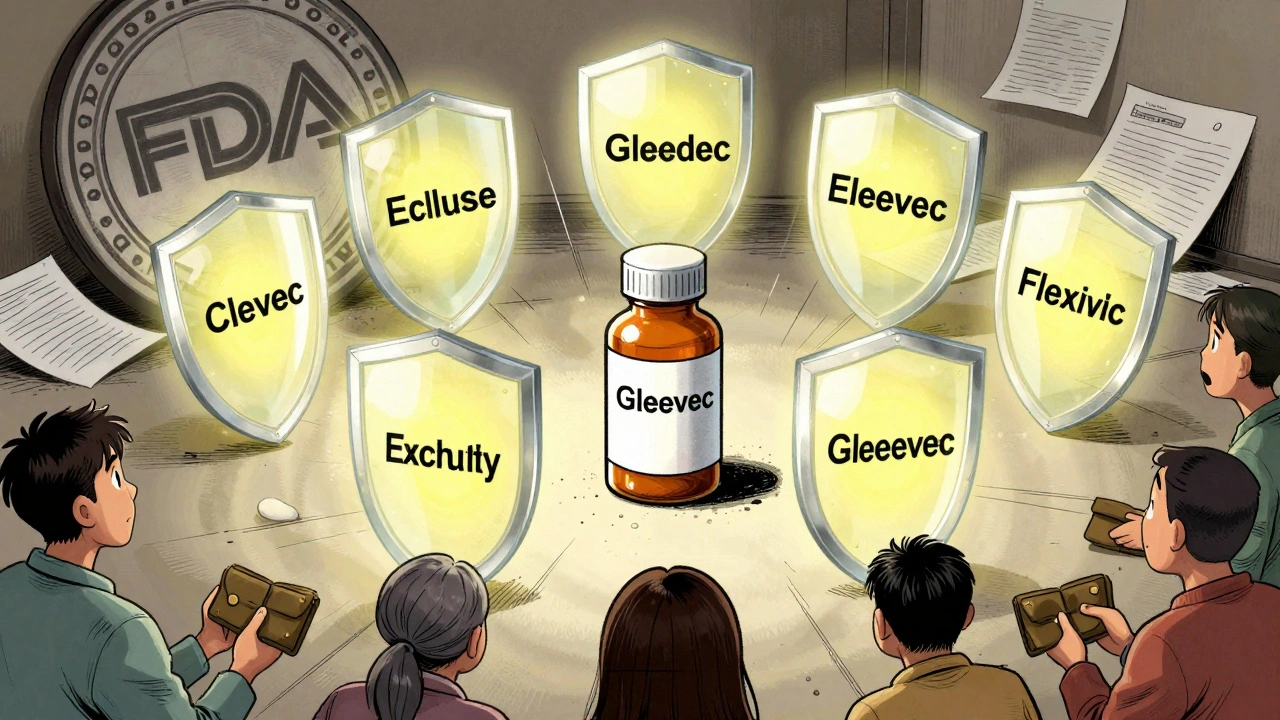

Market exclusivity is a government-granted monopoly that blocks generics from entering the market, even if no patent is in force. It’s not about invention-it’s about timing. The system was created in 1984 with the Hatch-Waxman Act to balance innovation and access. The idea was simple: give drugmakers enough time to recoup R&D costs, then let generics compete. But today, the system has been stretched thin.Take a drug like imatinib (Gleevec), used to treat leukemia. Its core patent expired in 2015. But thanks to a mix of orphan drug status, pediatric exclusivity, and secondary patents, generic versions didn’t arrive until 2022-seven years later. That’s not an exception. It’s the norm.

Companies don’t just rely on one extension. They stack them. A single drug can have orphan drug exclusivity, pediatric exclusivity, new indication exclusivity, and patent term extensions-all layered on top of each other. The result? A 20-year monopoly isn’t rare anymore. Some drugs, like tazarotene, have been shielded by 48 secondary patents after the original one ran out.

How the U.S. System Works

In the U.S., there are five main types of market exclusivity beyond patents:- New Chemical Entity (NCE) exclusivity: 5 years of protection for drugs with a completely new active ingredient. No generics allowed during this time, even if the patent expired.

- Orphan Drug exclusivity: 7 years for drugs treating diseases affecting fewer than 200,000 Americans. This is a huge incentive for rare disease treatments, but it’s also been used strategically-even for drugs that could treat more common conditions.

- New Clinical Investigation exclusivity: 3 years for new uses, dosages, or formulations of existing drugs. The catch? The FDA now demands real clinical benefit, not just minor tweaks.

- Pediatric exclusivity: An extra 6 months added to any existing exclusivity period if a company completes FDA-requested pediatric studies. This can push back generic entry by half a year, which can mean billions in extra revenue.

- Patent Challenge exclusivity: 180 days of exclusive rights for the first generic company to successfully challenge a patent. This is meant to encourage competition, but it’s often used as a bargaining chip in deals between brand and generic makers.

These aren’t optional. They’re automatic if you meet the criteria. But companies spend millions to make sure they meet them. A single pediatric study can cost $50 million. But if it adds 6 months of exclusivity to a blockbuster drug selling $3 billion a year? That’s a $1.5 billion payoff.

The European Union’s Different Approach

Europe doesn’t use the same system. Instead of multiple types of exclusivity, the EU relies mostly on one tool: the Supplemental Protection Certificate (SPC). It extends patent life by up to 5 years, with a maximum of 15 years of market protection after the drug is approved. If a company does pediatric studies, they get an extra 6 months-just like in the U.S.But here’s the big difference: the EU doesn’t stack exclusivities the way the U.S. does. You can’t get orphan drug exclusivity on top of an SPC. Instead, orphan drugs get 10 years of market exclusivity (12 if pediatric data is included). That’s longer than the U.S. 7-year version.

There’s also a special EU rule called Pediatric-Use Marketing Authorization (PUMA). If a drug was never patented but was developed specifically for kids, it gets 8 years of data protection plus 2 more years of market exclusivity. This is rare, but it’s a lifeline for small companies working on pediatric-only treatments.

Why This Matters: The Real Cost

You might think this is just a corporate game. But it hits your wallet. A 2023 study in JAMA Health Forum looked at just four drugs-bimatoprost, celecoxib, glatiramer, and imatinib. During the two years after generics should have entered, patients and insurers spent an extra $3.5 billion because exclusivity extensions blocked competition.That’s not a one-time spike. It’s the pattern. In 2022, 47 of the top 50 selling drugs in the U.S. had some form of exclusivity extension beyond their original patent. The average extension? 8.2 years. That means patients are paying brand prices for nearly a decade longer than the system was designed for.

And it’s getting worse. Evaluate Pharma predicts the average market exclusivity period for new drugs will hit 16.3 years by 2028-up from 12.7 years in 2018. That’s not innovation. That’s delay.

How Companies Game the System

It’s not just about filing paperwork. It’s about strategy.One common tactic is called product hopping. A company makes a tiny change to the drug-switches from a pill to a liquid, adds a new coating, changes the release timing-and then files for a new patent or exclusivity. Just before the original patent expires, they stop selling the old version and push the new one. Generics can’t copy it until the new exclusivity runs out. Teva reported that this tactic delayed generic entry for 17% of their target drugs.

Another trick is delayed patent filing. Instead of filing a patent right after discovery, companies wait until after Phase II trials. That way, the 20-year patent clock starts closer to when the drug hits the market. Instead of losing 10 years to clinical trials, they preserve most of the patent term for actual sales.

Then there’s the patent thicket. Companies file dozens of secondary patents covering everything from the shape of the pill to the way it’s packaged. These aren’t groundbreaking. They’re trivial. But they’re enough to scare off generics. One drug, celecoxib, had 12 patents filed after the original. Even if one gets invalidated, the others hold up.

Who Benefits? Who Loses?

Big pharma wins. The top 20 pharmaceutical companies all have teams of 15 to 25 people dedicated solely to managing exclusivity. They spend millions on legal and regulatory experts because every extra month of monopoly is worth millions.Biotech startups win too. A 2023 survey by the Biotechnology Innovation Organization found that 68% of startups say exclusivity extensions are critical to getting venture capital. Investors won’t fund a drug unless they see a clear path to 10+ years of sales.

Patient groups for rare diseases also benefit. Orphan drug exclusivity is the reason we have treatments for conditions like Duchenne muscular dystrophy and spinal muscular atrophy. Without it, no company would risk the $2 billion cost to develop a drug for 1,000 patients.

But everyone else loses. Patients pay more. Insurers pay more. Taxpayers pay more through Medicare and Medicaid. And generics manufacturers can’t compete until the exclusivity wall comes down-even if the drug has been on the market for 15 years.

Is the System Broken?

Critics say yes. The Yale Law and Policy Review called it a system that’s been “gamed well beyond the anticipated fourteen years.” The FDA itself admits exclusivity can extend protection “in the absence of patent protection”-meaning companies can block generics even if they never had a valid patent to begin with.The FTC is pushing back. In 2023, it filed a legal brief arguing that product hopping violates antitrust laws. The FDA tightened rules for 3-year exclusivity in April 2023, demanding real clinical benefit, not just cosmetic changes.

Europe is watching. In June 2023, the European Commission proposed reforming the SPC system to stop minor modifications from qualifying for extensions. The goal? Reward real innovation, not clever legal work.

But change is slow. The system is built into law. It’s not a glitch-it’s the design. And it’s working exactly as pharmaceutical companies planned.

What’s Next?

The pressure is growing. As drug prices keep rising, lawmakers are asking: Why do we let companies hold onto monopolies for 15, 18, even 20 years? The answer isn’t simple. Without exclusivity, fewer drugs for rare diseases would be developed. But without reform, everyday patients will keep paying inflated prices for drugs that should be cheap.The future may lie in transparency. What if every extension had to be published in plain language? What if the public could see how many patents a drug has, and how long each one delays generics? Right now, that information is buried in legal filings and FDA databases. Making it visible could force better behavior.

For now, the system stays. And the clock keeps ticking-for the next drug, the next patent, the next extension.

Constantine Vigderman

bro this is wild 😳 i had no idea companies could stack exclusivity like lego blocks. so imatinib was locked down for 7 years after patent expiry? that's not innovation, that's extortion.

Cole Newman

you think that's bad? wait till you find out how they use pediatric studies as a cash grab. $50M to get 6 extra months on a $3B drug? that's not science, that's a Ponzi scheme with a lab coat.

Tyrone Marshall

there's a deeper layer here. the system wasn't designed to fail-it was designed to be exploited. Hatch-Waxman was meant to balance access and incentive, but when the incentive becomes a weapon, the balance collapses. We're not just paying more for drugs-we're paying for a broken social contract.

Emily Haworth

this is all part of the shadow government. 🕵️♀️ big pharma owns the FDA, Congress, and half the judges. they wrote the rules so they can play forever. next they'll patent oxygen. 💊💀

Tom Zerkoff

The regulatory framework governing market exclusivity extensions was established with the intent of fostering innovation while ensuring timely market entry for generic alternatives. However, the current application of these mechanisms demonstrates a significant deviation from the original legislative intent, resulting in prolonged monopolistic control that undermines public health objectives.

Yatendra S

philosophically speaking, if a company doesn't innovate but just re-packages a drug, is it still a 'product'? or just a legal loophole dressed as medicine? 🤔

Himmat Singh

It is a fallacy to assume that market exclusivity extensions are inherently detrimental. Without such protections, the capital-intensive nature of pharmaceutical R&D would render many life-saving therapies economically unviable, particularly in rare disease indications where patient populations are minuscule.

kevin moranga

i get it, the system's messed up-but let’s not throw the baby out with the bathwater. orphan drug exclusivity saved my cousin’s life. the problem isn’t the tool, it’s how it’s being abused. maybe we need smarter rules, not total overhaul. like, if a drug treats 50k people, it shouldn’t get orphan status. simple fix. 🙏

Alvin Montanez

This isn't capitalism. This is feudalism with a corporate logo. Companies aren't inventing-they're renting time from the government. They're not curing diseases, they're harvesting human desperation. Every dollar spent on these extended monopolies is a dollar stolen from sick people who can't afford to live. This is moral bankruptcy dressed in white coats. And the FDA? They're the bouncers at the party where the rich get to hoard medicine.

Lara Tobin

i just feel so sad reading this. people are dying because of paperwork. 🥺 i know it's complicated but... how do we make it less broken? i just want people to get their meds without going into debt.

Jamie Clark

you’re all being naive. this isn’t about ethics-it’s about power. The system is working exactly as intended: to funnel wealth from the public to shareholders. The FDA doesn’t regulate-it rubber-stamps. The courts don’t adjudicate-they protect. The only thing that will change this is mass civil disobedience. Boycotts. Protests. Shutting down pharmacy chains. Until then, they win.

Keasha Trawick

this is the ultimate corporate magic trick: turn a molecule into a monopoly. 🎩✨ they take a chemical compound, slap on a 6-month pediatric study like glitter, then wave a patent thicket like a wizard’s cloak and say ‘abracadabra-no generics for 20 years!’ Meanwhile, grandma’s insulin costs more than her rent. It’s not science. It’s a heist with a peer-reviewed abstract.

Bruno Janssen

i just read this and cried. not because i'm emotional. because i know someone who died waiting for a generic. and the company knew. and they didn't care.