When you break out in hives after eating shrimp or feel dizzy after taking penicillin, it’s natural to assume you’re having an allergic reaction. But not all reactions are the same. Food allergies and medication allergies may look similar on the surface - itching, swelling, rashes, trouble breathing - but they’re different in how they happen, when they show up, and how they’re diagnosed. Mixing them up can lead to dangerous mistakes: avoiding life-saving drugs or eating something that could send you to the ER.

How Your Body Reacts: Immune System Differences

Both food and medication allergies involve your immune system overreacting to something harmless. But the way it reacts differs. About 90% of food allergies are IgE-mediated. That means your body makes a specific antibody called Immunoglobulin E that triggers mast cells to release histamine - the chemical that causes swelling, itching, and sometimes anaphylaxis. This is why symptoms like lip swelling or vomiting happen within minutes of eating the food.

Medication allergies are more complex. While about 80% of immediate reactions (like hives after an antibiotic) are also IgE-driven, the other 20% involve T-cells. These are delayed reactions that can take days or even weeks to show up. Think of a rash that appears three days after taking amoxicillin - that’s not an IgE reaction. It’s a T-cell response, often linked to conditions like DRESS syndrome or Stevens-Johnson syndrome. These are serious, but they don’t happen right after you swallow the pill.

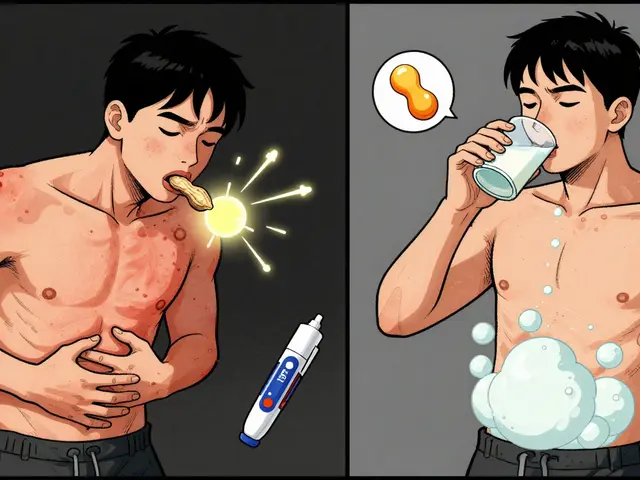

Timing: When Symptoms Show Up

Timing is one of the clearest clues. With food allergies, 95% of reactions happen within two hours - often within 20 minutes. If you eat peanuts and your throat closes up 15 minutes later, that’s textbook IgE-mediated food allergy. If you eat the same food again next week and the same thing happens, it’s almost certainly an allergy.

Medication reactions? They can be immediate - within an hour - but they can also be delayed. A rash from a sulfa drug might not show up until day three. A fever and swollen lymph nodes after taking allopurinol? That could be serum sickness, which peaks at 7-14 days. If you got sick after taking a drug once, but never had symptoms before, it’s harder to say whether it was truly an allergy or just a side effect or even a viral rash.

Symptoms: What to Look For

Food allergies often hit the mouth and gut first. Oral allergy syndrome - tingling or swelling of the lips, tongue, or throat - happens in about 70% of cases. Vomiting and diarrhea are common in kids. Hives are everywhere - 89% of reactions include them. Anaphylaxis can follow, especially with peanuts, tree nuts, shellfish, or milk.

Medication allergies more often show up as skin rashes. Maculopapular rashes (flat red spots with bumps) are the hallmark of delayed reactions. Hives can happen with immediate reactions, but respiratory symptoms like wheezing or low blood pressure are more common with medications than with food. Fever, joint pain, and swollen glands? Those point to a drug reaction, not a food one.

One big red flag: if you get a rash after taking a new antibiotic while you have a virus like mono or Epstein-Barr, it’s often not an allergy. Up to 90% of these rashes are harmless and mislabeled as penicillin allergy. That’s why so many people think they’re allergic to penicillin - but only 1 in 10 actually are.

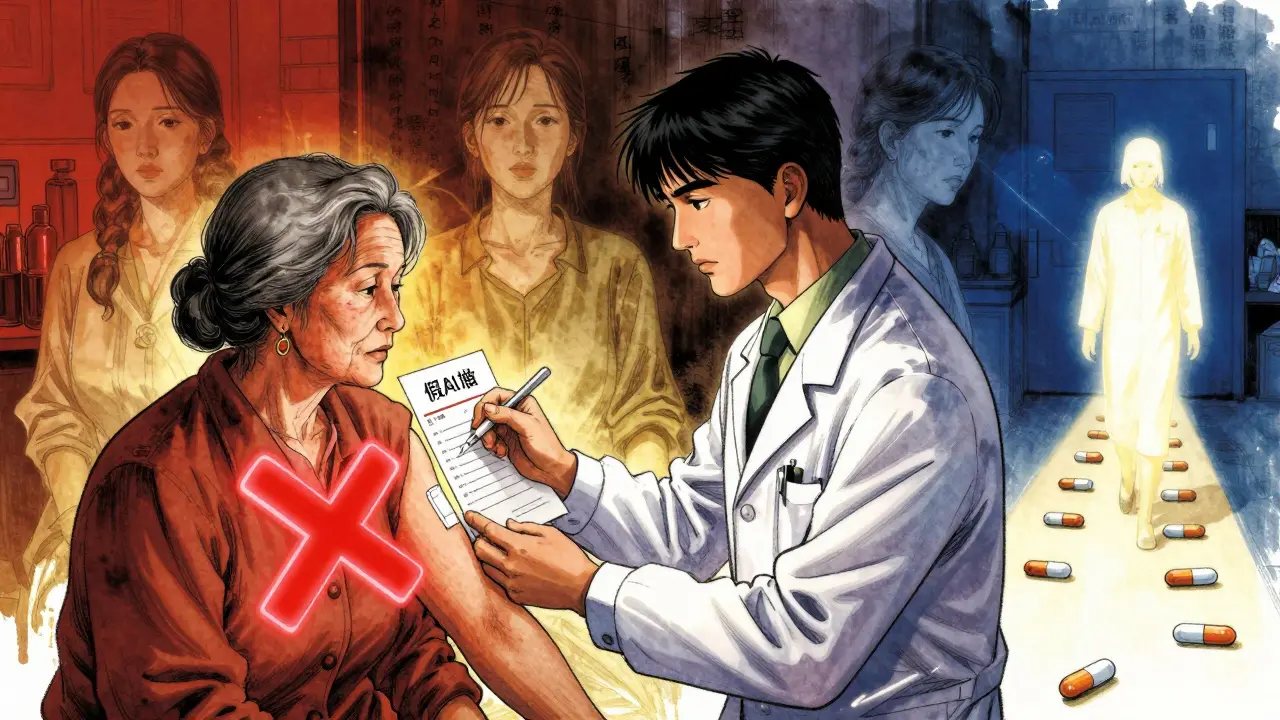

Diagnosis: Testing Is Key

For food allergies, the gold standard is skin prick testing and blood tests for IgE antibodies. But these aren’t perfect. A positive test doesn’t always mean you’ll react when you eat it. That’s why an oral food challenge - eating small amounts under medical supervision - is the only way to confirm it. It’s safe, accurate, and 95% reliable.

For medications, testing is trickier. Penicillin allergy testing is well-established: skin testing followed by an oral challenge if the skin test is negative. This combo is 99% accurate at ruling out true allergy. But for most other drugs - like NSAIDs, chemotherapy, or anticonvulsants - there’s no reliable test. Diagnosis comes down to your history, timing, and sometimes a supervised drug challenge in a hospital.

Here’s the scary part: up to 90% of people who say they’re allergic to penicillin aren’t. They had a rash as a kid, or got sick after taking it once, and were told they’re allergic. They’ve avoided penicillin for decades - even though it’s often the safest, cheapest, most effective antibiotic. Getting tested can open up better treatment options and reduce the risk of antibiotic-resistant infections.

Why Misdiagnosis Costs Lives - and Money

When a food allergy is mistaken for a stomach bug or reflux, people don’t carry epinephrine. That’s deadly. In the U.S., 150-200 people die each year from food-induced anaphylaxis, mostly because they didn’t recognize the signs or delayed using their EpiPen.

On the medication side, mislabeling leads to worse outcomes. People labeled as penicillin-allergic are often given broader-spectrum antibiotics like vancomycin or clindamycin. These drugs are 30% more expensive and increase the risk of C. diff infection by 25%. Hospitals that implement penicillin allergy delabeling programs cut broad-spectrum antibiotic use by 25% and save millions annually.

And it’s not just cost. One woman avoided all NSAIDs for 10 years because she thought she was allergic to aspirin. Turns out, her reaction was from the lactose in the pill - not the aspirin. She could’ve taken ibuprofen safely all along.

What You Can Do: Tracking and Talking

If you think you have an allergy, keep a detailed log. For food: write down exactly what you ate, when, and what symptoms appeared - down to the minute. Include preparation methods. Was the peanut butter roasted? Was the egg boiled or scrambled? Cross-contamination matters.

For medications: note the drug name, dose, when you took it, and when symptoms started. Did the rash appear after the first dose or the third? Did you have a fever? Was there a viral infection going on? These details help your allergist figure out if it’s a true allergy or something else.

Don’t assume. Don’t accept a label without proof. If you’ve been told you’re allergic to penicillin, ask for a referral to an allergist. If you’ve had a reaction to a food, get tested - especially if you’re a child. About 80% of kids outgrow milk and egg allergies by age 5. You might not need to avoid them forever.

What to Avoid

Don’t rely on internet forums or anecdotal stories. Reddit threads and Facebook groups can spread misinformation. One person’s reaction to a drug isn’t your blueprint.

Don’t self-diagnose. If you get a rash after eating sushi, don’t assume it’s shellfish. It could be a food intolerance, histamine poisoning, or even a reaction to the soy sauce.

Don’t avoid medications without testing. Avoiding penicillin because of a childhood rash isn’t protecting you - it’s limiting your care.

Final Takeaway

Food allergies are fast, reproducible, and often tied to specific proteins. Medication allergies are more variable - sometimes immediate, sometimes delayed, and often misdiagnosed. The key isn’t just knowing the symptoms. It’s knowing the pattern. When did it happen? How many times? What else was going on? That’s what turns a guess into a diagnosis.

Accurate diagnosis saves lives - whether it’s by letting you eat peanuts safely or by letting you take the right antibiotic when you’re sick. Don’t live with a label you don’t need. Get tested. Ask questions. And don’t let a past reaction define your future treatment.

Can you outgrow a food allergy?

Yes, many children outgrow allergies to milk, eggs, soy, and wheat - up to 80% by age 5. Peanut and tree nut allergies are less likely to be outgrown, but about 20% of kids do. Regular testing with an allergist can track whether you’ve developed tolerance. Blood tests and skin tests over time help determine if it’s safe to reintroduce the food under supervision.

Is a penicillin allergy real if I never had a reaction as an adult?

Many people are labeled with a penicillin allergy based on a childhood rash - often from a viral infection like mononucleosis, not the drug itself. Studies show 90% of people who report a penicillin allergy aren’t truly allergic. A simple skin test and oral challenge can confirm whether you can safely take penicillin or related antibiotics. If you’ve avoided it for years, testing could open up safer, cheaper treatment options.

Can a medication cause a rash without being an allergy?

Absolutely. Many drugs cause rashes as side effects, not allergic reactions. For example, amoxicillin often causes a non-allergic rash in people with Epstein-Barr virus - even though they’re not allergic to the drug. This is called a viral exanthem. It’s not dangerous and doesn’t mean you can’t take penicillin again. The key is timing and context. True allergic rashes usually appear within hours or days and may be itchy or spread quickly. Non-allergic rashes often appear later and aren’t accompanied by other symptoms like swelling or breathing trouble.

What’s the difference between a food allergy and food intolerance?

A food allergy involves the immune system and can be life-threatening - think anaphylaxis. A food intolerance doesn’t involve the immune system. Lactose intolerance, for example, is a digestive issue: your body lacks the enzyme to break down milk sugar. Symptoms are usually limited to bloating, gas, or diarrhea - not hives or swelling. Up to 20% of people who think they have a food allergy actually have an intolerance. Testing can tell the difference.

Should I carry an EpiPen if I think I have a food allergy?

If you’ve had a reaction that included swelling, trouble breathing, dizziness, or a drop in blood pressure - yes. Even if you’re unsure, it’s better to be safe. An EpiPen can save your life during anaphylaxis. If you’ve only had mild symptoms like a stomachache or a few hives, talk to an allergist before deciding. They can help determine your risk level and whether carrying an epinephrine auto-injector is necessary. Don’t wait for a severe reaction to take action.

Can I be allergic to both food and medication?

Yes. Having one type of allergy doesn’t protect you from another. Many people with food allergies also have drug allergies - and vice versa. The immune system can overreact to many different triggers. The key is to track each reaction separately. Keep a log of symptoms, timing, and possible triggers for both foods and medications. This helps your doctor spot patterns and avoid misdiagnosis.

How accurate are food allergy blood tests?

Blood tests for IgE antibodies (like ImmunoCAP) are good at detecting sensitization - meaning your body has made antibodies to a food. But they can’t confirm if you’ll have a reaction. About 30-50% of people with positive blood tests don’t react when they eat the food. That’s why an oral food challenge is still the gold standard. Blood tests are best used as a starting point, not a final diagnosis.

Why is it hard to test for most drug allergies?

Unlike food allergies, most drug allergies don’t have reliable skin or blood tests. The immune response is more complex and varies by drug. For penicillin, we have good tests. For others - like sulfa drugs, NSAIDs, or chemotherapy - we often have to rely on your history and a controlled challenge in a hospital setting. This is risky, so it’s only done when necessary. That’s why many drug allergies are misdiagnosed - not because doctors are careless, but because the tools are limited.

Edith Brederode

This is so helpful!! 🙌 I always thought my rash after amoxicillin was an allergy, but now I realize it might’ve been from the virus I had. Gonna ask my doctor about testing!

Art Gar

The premise of this article is fundamentally flawed. Allergies are not 'immune overreactions'-they are the result of pharmaceutical-industrial manipulation of our microbiomes. The IgE narrative is a convenient myth to sell epinephrine pens and skin tests. Real healing comes from fasting and grounding.

clifford hoang

So let me get this straight... the system tells us we're allergic to penicillin so we avoid it... then they give us vancomycin which is 30% more expensive and causes C. diff... and you're telling me this isn't a profit-driven ploy? 🤔 The FDA, Big Pharma, and your allergist are all in on it. They want you dependent on expensive drugs. I've been tracking my symptoms since 2018. The pattern is CLEAR.

Emily Leigh

I mean... I guess? But like, who even has time to keep a log of every single bite and pill? I just avoid stuff that makes me feel weird. And if I get a rash? That’s it-I’m never taking that drug again. Simple.

Renee Stringer

The notion that 90% of penicillin allergies are misdiagnosed is statistically dubious. Without double-blind, placebo-controlled challenges across diverse populations, such claims are speculative. Medical labels should not be discarded lightly.

Crystal August

I had a rash after penicillin at age 6. I’m 42 now. I’ve avoided every antibiotic in that class for 36 years. You think I’m just gonna let some doctor poke me with a needle and swallow a pill? No. I’ve lived fine without it. Don’t mess with my health.

Nadia Watson

Thank you for this. I'm from India and we don't have easy access to allergists here. This breakdown helps me explain to my cousin why her son's reaction to peanuts isn't just 'bad digestion'. I'm sharing this with my local clinic.

Also-typos happen. I typed 'anaphylaxis' as 'anaphalaxis' just now. Oops. But the point stands. We need better awareness.

Courtney Carra

It’s fascinating how we’ve turned biological responses into identity markers. 'I’m allergic to shellfish' becomes 'I am a person who cannot eat shellfish'-and then it becomes a moral stance. What if the real issue isn’t the food, but the industrial processing? The histamine overload? The environmental toxins we ingest daily? We’re diagnosing symptoms, not causes.

thomas wall

I must express my profound concern regarding the casual dismissal of patient-reported histories. To suggest that 90% of penicillin allergies are false is not only medically irresponsible-it is dangerously dismissive of lived experience. Anecdotes are not data, but neither is statistical abstraction a substitute for clinical empathy.

Shane McGriff

I used to think I was allergic to eggs until I got tested. Turns out, I just had a mild intolerance. I didn’t even know the difference.

If you’ve ever had a reaction and just assumed it was an allergy-please, get tested. It’s not scary. It’s life-changing. You might be avoiding something you don’t need to. I was. And now I eat scrambled eggs like a normal human.

Paul Barnes

The article correctly distinguishes between IgE-mediated and T-cell-mediated reactions. However, the claim that 'up to 90% of people who say they’re allergic to penicillin aren’t' is misleading without citing the source population. The 90% figure applies only to patients referred for allergy evaluation, not the general public.

Edith Brederode

Shane, your story gave me chills 😭 I’m getting tested next week. Thank you for saying this.