Every year, tens of thousands of children under five end up in emergency rooms because they got into medicine they weren’t supposed to. It’s not because parents are careless-it’s because the risks are hidden in plain sight. A bottle left on the nightstand. A teaspoon used to measure liquid medicine. A child-resistant cap that wasn’t clicked shut. These aren’t rare mistakes. They’re common, preventable, and often deadly.

Why Kids Under Five Are at Highest Risk

Children under five are natural explorers. They put things in their mouths to learn about the world. That’s normal. But when that world includes medicine bottles, it becomes dangerous. According to CDC data, emergency visits for accidental medication exposure in this age group peaked at over 76,000 in 2010-and while numbers have dropped since, they’re still far too high. The problem isn’t just access. It’s confusion. Many parents don’t realize that “child-resistant” doesn’t mean “child-proof.” The Consumer Product Safety Commission found that 10% of kids can open these caps by age 3.5. And even when caps are secured, kids can reach meds stored on countertops, in purses, or on bathroom shelves.The Three-Part Solution: Packaging, Labels, and Education

The CDC’s PROTECT Initiative-launched in 2008-is the most effective national effort to tackle this issue. It works on three fronts:- Packaging improvements: Child-resistant caps must be twisted until they click. Flow restrictors-small plastic inserts inside bottles-slow down liquid flow so kids can’t gulp down a full dose. But not all medications have them yet. Liquid acetaminophen and diphenhydramine are still top offenders.

- Standardized labels: Since 2019, federal rules require all pediatric liquid medications to list doses in milliliters (mL) only. No more teaspoons or tablespoons. This cuts down confusion. Yet, many older bottles and home dosing tools still use teaspoons, which vary in size. A kitchen teaspoon can hold anywhere from 3 to 7 mL. That’s a dangerous gap.

- Education campaigns: The “Up and Away and Out of Sight” program tells caregivers to store meds in locked cabinets, at least 4 feet off the ground. It sounds simple. But only 32% of households do it consistently, according to a 2022 national survey.

How to Store Medicines Safely

Storing medicine isn’t just about putting it away. It’s about making sure it’s impossible for a child to get to-even if they climb, open drawers, or mimic adults.- Always keep meds in their original containers. Labels have vital info like dosage, expiration, and warnings.

- Use locked cabinets or boxes with childproof latches. A high shelf isn’t enough. Kids climb.

- Never leave medicine on nightstands, countertops, or in purses-even for a minute. A 2023 Reddit post from a parent described how their 2-year-old swallowed blood pressure pills because they were left on the nightstand after a doctor’s visit. That parent now keeps everything locked.

- Store all meds, including vitamins and supplements. Many parents think “it’s just a vitamin,” but even high doses of vitamin D or iron can be toxic to kids.

How to Dose Correctly

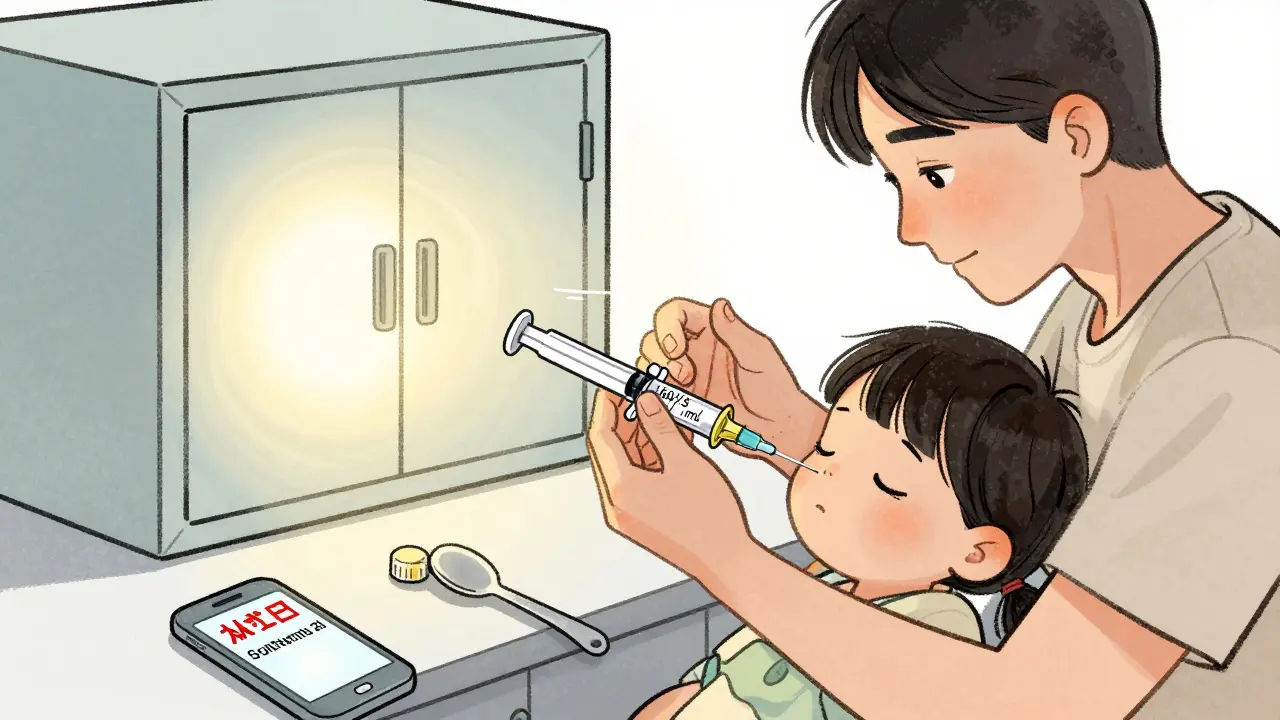

One of the biggest causes of overdose? Using the wrong tool to measure liquid medicine.- Use only the dosing device that came with the medicine-syringe, cup, or dropper. Never a kitchen spoon.

- Check the concentration. Infant acetaminophen is 160 mg/5 mL. Children’s acetaminophen is 160 mg/5 mL too-but some older bottles say 80 mg/5 mL. Mixing them up leads to double dosing.

- Write down the dose and time on your phone or a notepad. It’s easy to forget what you already gave, especially when a child is sick and you’re tired.

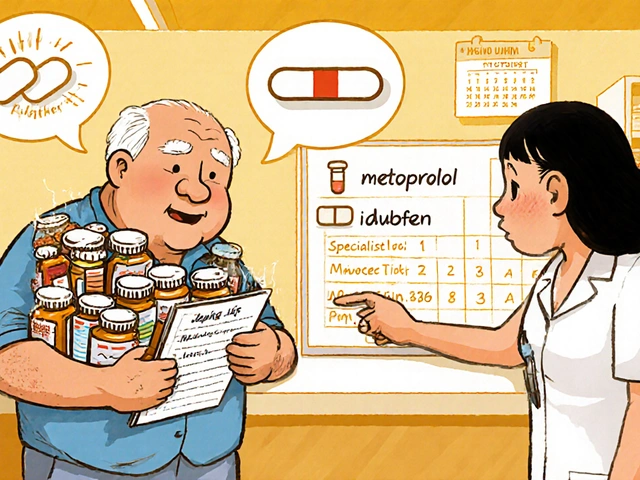

- Ask your pharmacist: “Is this the same strength as the last bottle?” If they hesitate, double-check.

Research in Pediatrics found that 40% of parents make at least one dosing error. Most of these happen with liquids. The fix? Trust the tool that came with the bottle-not your memory or your kitchen.

What to Do If Your Child Gets Into Medicine

If you suspect your child swallowed medicine-even if they seem fine-act fast.- Call Poison Control immediately: 1-800-222-1222. This is free, confidential, and available 24/7. Don’t wait for symptoms.

- Don’t make your child vomit. It can cause more harm.

- Keep the medicine bottle. Emergency staff need to know exactly what was taken, how much, and when.

- If it’s an opioid (like oxycodone or hydrocodone) and your child is unresponsive, not breathing, or turning blue, give naloxone if you have it. The SAMHSA Overdose Prevention Toolkit now includes clear instructions for using naloxone in children. Intranasal sprays are safe for kids as young as infants.

Many parents don’t know naloxone can be used for children. The FDA approved it for kids years ago, but most doctors don’t prescribe it unless the child is on opioids. That’s changing. As of February 2024, the American Academy of Pediatrics now recommends co-prescribing naloxone with every opioid prescription for children.

What’s Still Not Working

Progress has been made-but gaps remain.- Only 58% of households use child-resistant caps correctly.

- Just 63% of pediatricians talk about safe storage during well-child visits.

- Flow restrictors aren’t required on all liquid meds. Opioids are getting them in 2025, but other drugs like cough syrups still don’t have them.

- Safe disposal programs are inconsistent. Many people keep unused meds “just in case,” even though expired or leftover drugs are a major source of accidental exposure.

There are smart solutions out there-like Hero Health’s automated dispenser or AdhereIT’s connected packaging-but they cost hundreds of dollars. Most families can’t afford them. Prevention needs to be low-cost, simple, and available to everyone.

What’s Next

The CDC’s Healthy People 2030 goal is to reduce pediatric medication overdoses by 10% from 2019 levels. By 2023, they’d already hit a 6.2% drop. That’s progress. But with 14,000-20,000 preventable ER visits still expected each year by 2030, we’re not done. The Up and Away campaign is expanding into 12 new languages by 2026. The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists will release its first-ever Pediatric Medication Safety Best Practices Guide in late 2024. And the FDA is pushing for flow restrictors on all liquid pediatric meds. These changes matter. But they won’t save lives unless parents, caregivers, and providers use them.Final Checklist: 5 Steps to Prevent Accidental Overdose

1. Lock it up - Keep all meds in a locked cabinet, out of sight and reach. 2. Use the right tool - Only use the dosing device that came with the medicine. Never a spoon. 3. Check the label - Confirm the strength (mL) and don’t mix infant and children’s formulas. 4. Dispose safely - Use a drug take-back program. If none is available, mix pills with coffee grounds or cat litter, seal in a bag, and throw in the trash. 5. Know the number - Save 1-800-222-1222 in your phone. Call it before you panic.Accidental overdose isn’t a failure of love. It’s a failure of systems. But we can fix it-with better packaging, clearer labels, smarter storage, and quicker action. You don’t need to be perfect. You just need to be consistent.

Can child-resistant caps really stop a toddler?

No. Child-resistant caps are designed to slow down children, not stop them completely. Testing shows 10% of kids can open them by age 3.5. That’s why storing medicine in a locked cabinet is just as important as using the cap correctly. Always assume your child can get in if it’s within reach.

Is it safe to use a kitchen spoon to measure liquid medicine?

No. Kitchen spoons vary in size-anywhere from 3 to 7 milliliters. A teaspoon of medicine could be half a dose or double. Always use the dosing syringe, cup, or dropper that came with the medicine. These are marked in milliliters and calibrated for accuracy.

What should I do if my child swallows a whole pill?

Call Poison Control at 1-800-222-1222 right away-even if your child seems fine. Some medications cause delayed reactions. Keep the pill bottle. Emergency staff need to know the name, strength, and how many were taken. Don’t try to make your child vomit unless instructed by a professional.

Can I give naloxone to a child who overdosed on opioids?

Yes. Naloxone is safe and approved for children of all ages. If your child is unresponsive, not breathing, or has blue lips, give naloxone immediately if you have it. Use the intranasal spray as directed-no special adjustments needed for kids. Then call 911. Naloxone can save a life while you wait for help.

How do I dispose of old or unused medications safely?

Use a drug take-back program if one is available in your area-many pharmacies and police stations offer them. If not, mix pills with something unappealing like coffee grounds or cat litter, put them in a sealed bag, and throw them in the trash. Don’t flush them unless the label says it’s safe. Flushing can contaminate water supplies.

Tom Swinton

Okay, I just read this and I’m sitting here with my heart in my throat-because I’ve done ALL of these things wrong. I’ve left cough syrup on the nightstand after my daughter’s fever spike. I’ve used a kitchen teaspoon because the syringe was ‘somewhere in the drawer.’ I thought ‘child-resistant’ meant ‘my toddler can’t open it’-and now I know that 10% of kids can crack those caps by age 3.5?!?! That’s not a safety feature-that’s a psychological trap! I’m buying a locked cabinet tonight. I’m throwing out all my old dosing spoons. I’m saving Poison Control in my phone under ‘EMERGENCY’-not ‘Medicine Stuff.’ And I’m telling every parent I know. This isn’t fear-mongering-it’s survival. We owe our kids better than assumptions.

Mukesh Pareek

The pharmacovigilance framework surrounding pediatric OTC formulations remains egregiously fragmented. While the CDC’s PROTECT initiative has made incremental strides, the absence of mandatory flow restrictors across all liquid formulations-particularly in antihistaminic and antitussive agents-constitutes a systemic failure in risk mitigation. The regulatory arbitrage between opioid and non-opioid pediatric suspensions is indefensible. Furthermore, the persistence of mL/teaspoon ambiguity in consumer-facing labeling, even post-2019 FDA mandate, reflects a profound disconnect between policy and implementation. Until universal standardization is enforced via federal mandate-with penalties for noncompliance-this epidemic will persist as a function of logistical negligence, not parental malfeasance.

Leonard Shit

lol so i left my blood pressure pills on the counter for 2 minutes… and my 2yo got them. i thought ‘they’re just pills’… turns out they’re not. now i have a locked box in the closet and a syringe that looks like a spaceship. also i called poison control just to say hi. they were nice. also also: my kid opened the ‘childproof’ cap. it took 47 seconds. i’m not mad. i’m just… really tired now.

Gabrielle Panchev

Wait-so you’re telling me that ‘child-resistant’ doesn’t mean ‘child-proof’? And that we’re supposed to trust a system that’s designed to be ‘resistant’-not ‘impenetrable’-when our children are natural climbers, explorers, and mimickers? That’s not safety-that’s a cruel joke. And don’t even get me started on the ‘just keep it on a high shelf’ advice. My niece climbed a bookshelf to get her grandma’s vitamins-and swallowed 14 iron pills. She’s fine now. But she almost died because someone thought ‘high’ was enough. And now you want me to believe that a $300 smart dispenser is the solution? No. The solution is mandatory flow restrictors, plain labels, and locked cabinets-with federal funding to make them accessible to EVERY family-not just the ones who can afford it. This isn’t about parenting. It’s about policy failure.

Kiran Plaha

i never knew that vitamins can be dangerous. i thought only real medicine was bad. now i keep all my wife’s omega-3 and my iron pills locked. also, i use the syringe now. no more spoons. i feel stupid for not knowing this. but now i know. thank you.

Matt Beck

we’re all just one distracted moment away from a nightmare 🤯 and yet we treat medicine like it’s a snack. i mean… a 2-year-old sees a pill on the nightstand and thinks ‘ooh shiny!’ and boom-emergency room. why are we still using teaspoons? why are flow restrictors optional? why is naloxone not in every home like fire extinguishers? we fix car seats. we install smoke alarms. but we let our kids play Russian roulette with ibuprofen? 🤦♂️ we need a national campaign: ‘Lock It. Measure It. Call It.’ and make it as mandatory as seatbelts. because love isn’t enough. systems are.

Kelly Beck

Reading this made me cry-not because I’m scared, but because I’m so proud of how far we’ve come in awareness. I used to think ‘my kid’s too smart to get into medicine’-until she opened my purse and found my anxiety pills. Now I have a locked cabinet, a labeled dosing chart on the fridge, and I check every bottle before I put it down. I’ve even started a little ‘Medicine Safety Circle’ with my mom friends-we swap tips, share stories, and remind each other: it’s not about being perfect, it’s about being consistent. And if you’re reading this and thinking ‘I’m not that careless’-you’re already halfway there. Keep going. You’re doing better than you think. 💪❤️

Katelyn Slack

i just want to say thank you for writing this. i used to think it was my fault when my son got into his sister’s allergy medicine. i felt so guilty. but reading this made me realize it’s not about blame-it’s about systems. i’m buying a lockbox this weekend. and i’m putting poison control on speed dial. you’re right. we just need to be consistent. thank you for not making me feel like a bad mom.

Venkataramanan Viswanathan

In India, we often store medicines in open cupboards, believing that children will avoid them out of respect or fear. This is a dangerous misconception. In our rural clinics, we have seen toddlers ingest antimalarials and antibiotics from unsecured shelves. The solution is not only education but community-level intervention-local health workers must distribute low-cost lockboxes during immunization visits. We must also translate ‘Up and Away’ into regional languages. A mother in Bihar who cannot read English must still know: medicine must be locked. This is not a Western problem. It is a human problem. And it demands a global response.